Personally, I’ve always liked bicycles.

When I was a lot younger than I am now a bicycle gave me a freedom to explore, as well as providing cheap and reliable transport.

And because I’ve always had a soft spot for bicycles, I’ve also been interested in the history of cycling.

Bicycles were really important at the end of the nineteenth century to both men and women.

To women, because they gave women the freedom to travel without a male chaperone and allowed them to travel independently. To men, especially working class men, they provided both cheap transport and a way of getting out of industrial towns and their pollution.

But one aspect that had totally escaped my attention was their role in warfare.

Army Cyclist badge, Auckland Museum, Public domain via Wikimedia commons

In fact I only really came across the use of bicycles by the British Army in the first world war when I read Ursula Bloom’s memoir, when she mentions that someone that she knew had joined a cyclist’s battalion.

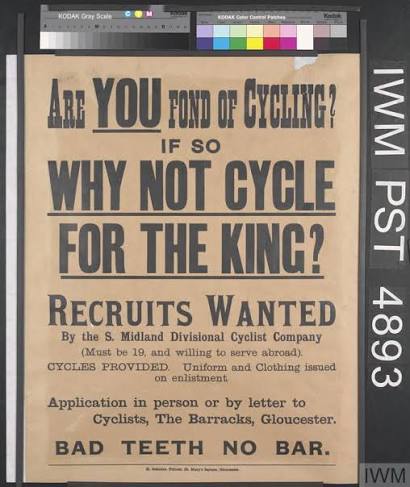

Image: Imperial War Museum, London

So what were they?

Richard Holmes “Tommy”, his history of British soldiers on the western front in world war one provides a little more detail explaining that cyclist’s battalions were recruited primarily as messengers – radio was in its infancy, and field telephone lines were in continual danger of being broken by shellfire – hence the use of cyclists carrying messages back from the front to the officers behind the lines and also to the artillery.

Indian soldier cyclists during the battle of the Somme, 1916 via the IWM Wikimedia commons image collection

In such a static war as world war one, bicycle soldiers were not used by the British due to their mobility but other armies have used soldiers on bicycles and a cheap and efficient way of moving troops.

In 1940, Danish soldiers used bicycles to ride to war before being overwhelmed by the Wehrmacht, and the Japanese, when they invaded Malaysia confiscated bicycles and gave them to their soldiers as a way of moving their army.

Tellingly, both Sweden and Switzerland maintained bicycle detachments until the last quarter of the twentieth century, with Switzerland ending their use in the 1970s and Sweden in the early 1980s.

Both armies used custom made, easy to maintain bicycles and also bicycle trailers to transport heavier and bulkier items.

Swedish soldiers carrying anti tank missiles on bicycles – Wikimedia commons

And from the Swedish and Swiss perspective their use made perfect sense.

During wartime, even if they were able to maintain their neutrality, fuel would be scarce (Sweden, Finland and the USSR maintained a strategic reserve of steam locomotives during the cold war as a buffer against fuel shortages. Incidentally, despite rumours to the contrary the United Kingdom did not.), and in a country with well maintained roads, bicycles would provide a cheap and effective way of moving soldiers.

By using simple single speed bicycles that need little in the way of specialist maintenance, or indeed any maintenance beyond fixing punctures and keeping the chain clean and lubricated.

In a time when bicycles were still used as transportation, changing a tyre or an inner tube would be a skill most people would already have.

Swedish conscripts fixing their bicycles – Swedish Army museum via Wikimedia commons

And as experience in the Vietnam war showed, bicycles can be incredibly valuable as a means of transporting supplies, especially during a partisan or asymmetric conflict.

And bicycle warfare does not just belong to history, there are unconfirmed reports of Ukrainian soldiers in the current conflict using bicycles to transport attack drones to the front line…