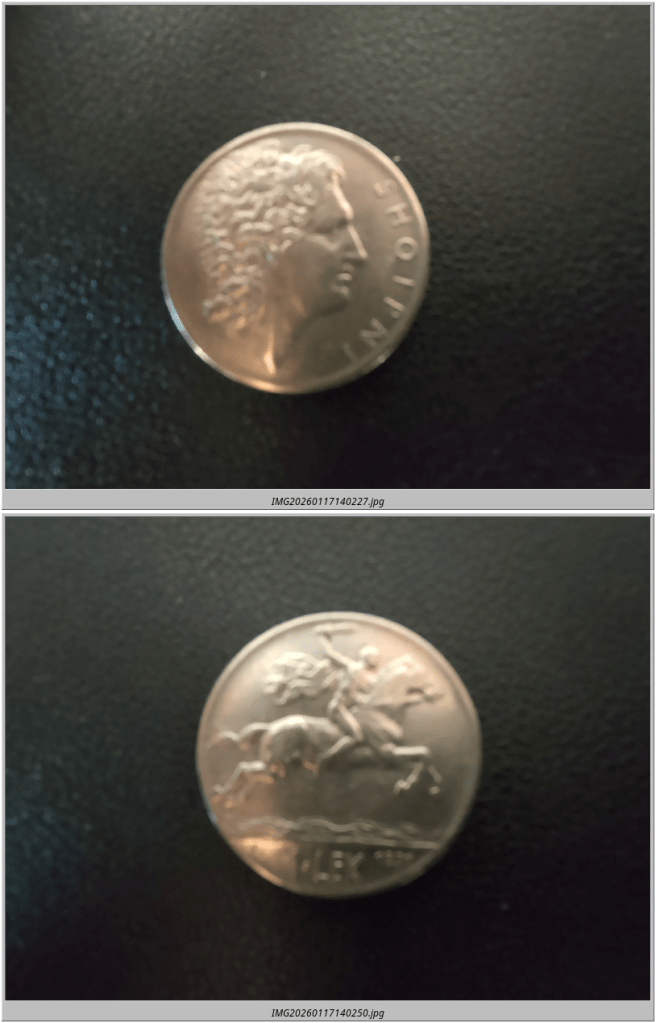

I’m about half way through ‘If you’re reading this, I’m already dead’, a novel very loosely based on Otto Witte, the acrobat who aspired to become King of Albania in the chaos of Albania’s independence after the Balkan Wars that preceded world war one.

The novel is very silly, but makes for a decent bedtime read.

In the course of the novel, when the hapless group of circus escapees finally arrive in Albania, accompanied by a camel (don’t ask why, this is fiction, not history), they encounter a British spy called Sandy Arbuthnot.

My ears pricked up at this point. I’d read Greenmantle by John Buchan a few weeks ago and that book also features a character known as Sandy Arbuthnot, one of these Empire types who ‘knocks about’ in the backwoods of the Balkans and Turkey, and even if he’s not exactly a spy, he’s certainly a player in the Great Game.

Like the later travel writer Eric Newby, if Arbuthnot was a real person, there would always be a suspicion that he had some sort of connection with British Intelligence.

And then I did something silly.

I typed the string “Sandy Arbuthnot” into wikipedia’s search box.

And there we have it, the undoubtedly fictional Sandy Arbuthnot has his own Wikipedia page.

But it also reveals a more interesting story. John Buchan’s character Sandy Arbuthnot was based (mostly) on Aubrey Herbert, who not only spent a considerable part of his life travelling in Albania and Turkey, was most definitely a player in the Middle Eastern politics of the time, especially during the first world war.

A friend of TE Lawrence, Herbert knew most of the major players in the jockeying for power in the wake of the first world war in the Middle East, and in a you couldn’t make this up moment was apparently offered the throne of Albania.

Twice.

Herbert died young, in 1923 from blood poisoning, just a few months after his brother, George Herbert, Lord Carnarvon, who sponsored Howard Carter’s dig for the tomb of Tutankhamun, died in Cairo from an infected mosquito bite.

Not the man who would be king, but most definitely the man who could have been king…