While I was researching something else entirely, I had this light bulb moment about trams, and why they were a product of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras.

A tram in Launceston Tasmania on a sunny Edwardian afternoon

A lot of large nineteenth century cities had cobbled streets in the city centre, and these relatively smooth streets allowed the operation of horse buses.

Crinolines and horse buses

Horse buses were cramped and could not carry more than a few people at a time.

However quite a few streets were simply gravelled, and some had a surface that was not much better than that of a dirt road today and basically horse buses didn’t cope well with rough surfaces and potholes.

So, in quite a few places they had horse trams – the lightweight track ensured a smooth ride and the horses could pull a heavier load.

Horse tram in Darlington England

Horses of course needed to be looked after, fed, and rested, which meant that even horse trams could not carry that many people, and were not particularly cheap.

And then, on the back of demand for the new electric lighting, cities began to acquire power plants. Sometimes these were privately owned an operated, and sometimes they were publicly owned by the local authority.

Suddenly there was a source of readily available motive power that didn’t need to be fed and watered, so it seemed like a no brainer to convert the horse tram systems to electric operation – in some cases as in Dundee in Scotland where the city owned the Carolina Port power plant they took over the tram system and expanded it, in other places the tram system remained in private hands, and there are instances such as Falkirk again in Scotland, where the tram system was actually built by the local power company.

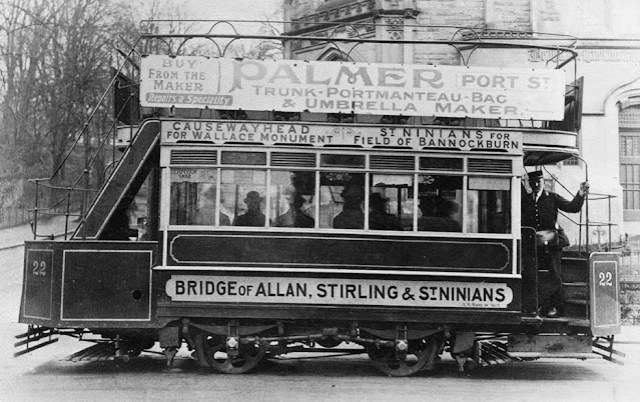

All of this happened unevenly – there were places, like Stirling, yet again in Scotland where the horse tram system was never electrified, and the horses were eventually replaced by petrol engines.

Look Ma! No wires! Petrol powered tram in Stirling

And that’s a key observation – by the 1890s overhead transmission lines and electric power was a mature technology. Internal combustion engines were not reliable enough or powerful enough to power public transport until roughly 1910, when motor buses began to appear.

But again they needed a relatively smooth surface, so it was not until after the first world war when increasing car use led to city streets being sealed with bitumen that they really became a viable option.

Approaching Queen Victoria Street in York

At the same time trams were beginning to be a problem.

Most tram systems dated back to just before 1900 – a few were later – but it’s true to say that by 1920 a lot of the systems were in need of maintenance, especially as maintenance had been skipped during the first world war, leading to a backlog of track repairs and worn out trams well past their use by date.

Trams, cars, and buses in Museum Street York some time in the 1920s

Buses were cheaper to operate, and didn’t run on tracks down the middle of the road – what seemed a great idea in 1890, running the tramline down the middle of the street to avoid bicycles and horse drawn delivery carts didn’t seem such a good idea in in the 1920’s with the increasing use of motor vehicles, especially when dealing with narrow European city streets.

And so tram systems began gradually to be closed down and replaced by buses.

Sometimes the ghosts of long vanished tram systems can still be seen – for years there were still tram tracks running down the middle of High Street in Dundee, and as late as the early 2000s there were still sections of track poking through the bitumen on Great Western Road in Glasgow, forty years after the last tram rattled down towards the city centre …