The combination of the penny post and increasing literacy meant that people in the nineteenth century wrote a lot.

We are not talking about the good and the great, but about ordinary people writing ordinary letters commiserating a cousin for the death of a loved one, or a letter to a son or daughter who has moved away, or even a postcard to confirm the safe arrival of a brace of pigeons.

Ordinary letters about ordinary things.

If you search for nineteenth century postal ephemera, letters, envelopes, postcards on antique websites, they will almost always be written in black, probably iron gall, ink, much as official documents of the time were written.

And you might be forgiven for thinking that most people wrote in ink.

But writing in ink in the nineteenth century was a messy business.

First of all you needed a bottle of ink and a dip pen, and possibly some blotting paper. Rather than writing on a flat surface as we do, if you were sophisticated, you used a either a desk or a writing box with a slope to it, the idea being that if you used a slope it was easier to sit upright and avoid accidentally blotting what you had written on the previous line with your cuff.

(I can remember sixty or so years ago in Scotland my first primary school still had desks with a slope to them and inkwells, even though by then the ball point pen had done away with the dip pen.)

And it’s true that most nineteenth century run of the mill writing that has survived was done in ink.

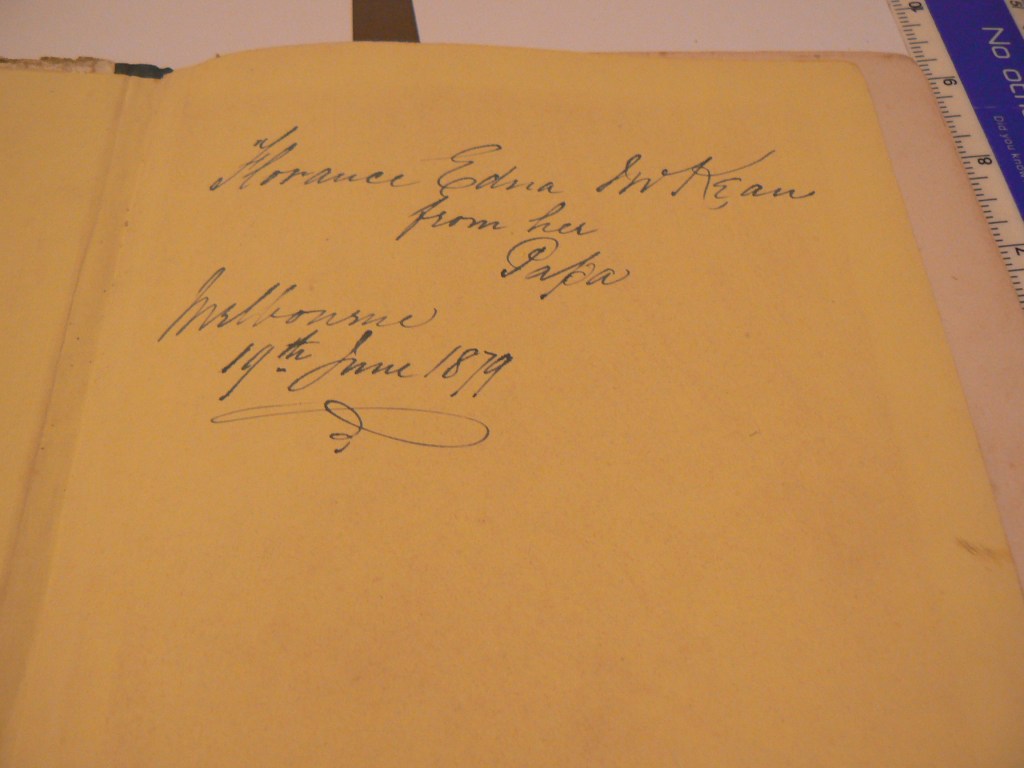

But when, up at the Athenaeum, I was looking at the prayer books and bibles from deconsecrated churches I noticed something – when people wrote their name inside a prayerbook they usually wrote it in ink, just as when down a Lake View some of the books used as props have dedications in them, they are usually written in ink.

But the old prayer books are different. Some do have doodles in ink, but mostly the graffiti, the caricatures, the drawings of genitalia, and even some of the random comments written in the margins are in pencil.

There’s even a shopping list in pencil in the back of one of them, doubtless written during a particularly boring sermon.

Pencil had the benefit of being spontaneous, and ideally suited to writing notes on bits of scrap paper, totting up an invoice, and doodling in a moment of boredom, basically the sort of stuff that doesn’t survive, but instead is used to light the fire when done with.

But if you look through collectors trading sites you do occasionally come across postcards written in pencil that have survived – remember that nineteenth century people used postcards much as we use text messages and emails – they might be mundane requests to the local hardware store for a pound of No. 6 nails to be added to the farm’s account, or a scribbled note from a country vicar telling his wife that he has had to stay an extra day in Melbourne, but he will be home to take Evensong on Friday.

And we know people used pencils, as quite a few luxury propelling pencils from the Victorian era have survived and are now collectors items.

And people wouldn’t have made and sold luxury propelling pencils unless there was a market for them among the middle classes.

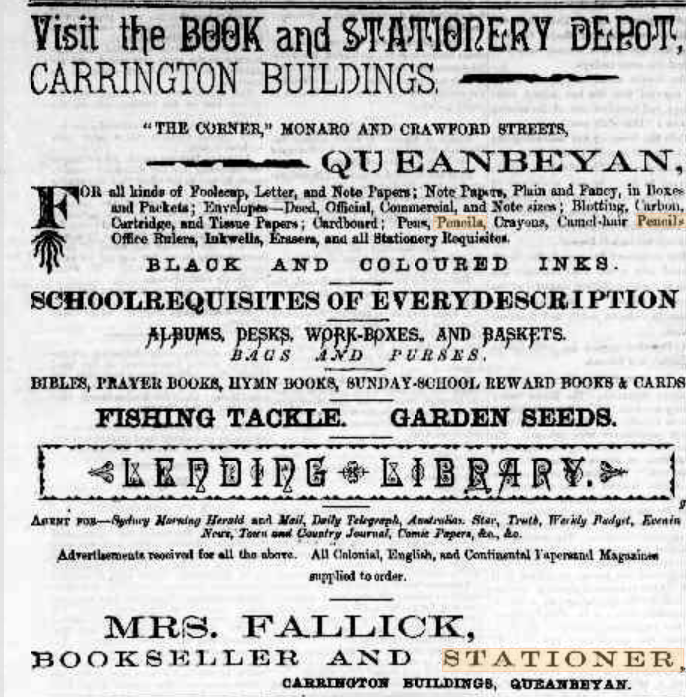

What we don’t have are ordinary wood and graphite pencils, because on the whole they were used and when they were no more than an unusable stub, thrown away, but stationers’ adverts from the time routinely list them.

So, while nineteenth century people did write in ink, they didn’t only write in ink, often they also wrote in pencil …