The Edwardian era was an unsettling time for Britain.

Queen Victoria had died, and with her the certainties of the late Victorian era. People were unsure of what, exactly, was Britain’s place in the world, and if there would be a war.

And you see this reflected in the popular fiction of the time. One trope was ‘invasion fiction’, such as Erskine Childers’ Riddle in the Sands, a variant on espionage fiction where some dastardly foreign power, usually Germany (after all Britain was locked in a naval arms race with Germany, as expensive and deadly as the later Soviet US arms race), was going to mount a sneaky invasion and overwhelm an incompetent and bumbling British government, and square jawed chaps would have to take it on themselves to do something about it.

And in the Edwardian era Britain, fearing attack, made alliances.

First with France, despite lingering suspicions dating back to the Napoleonic era, not to mention some more recent colonial disputes, but at least they could agree that Germany was a threat to them both.

Britain’s other ally was Imperial Russia, the third member of the triple entente.

Russia was a nasty repressive autocratic state.

People disappeared, people were sent in exile to Siberia, but yet there was money to be made as the Russian economy was beginning to boom, new factories, a new middle class, railways to be built, and so on.

At the same time there were all these escapees from Russia. Some were poor Jews fleeing persecution, some were equally poor political dissidents choosing life in the East End of London over internal exile, or worse a labour camp somewhere in the trackless wastes of Siberia.

Tolerated, Edwardian Britain was quite liberal in allowing dissidents and exiles in, something that was recognised by at least some of the exile groups, including the RSDLP, the forerunner of the Bolsheviks. The RSDLP, who were appreciative of being able to hold their congresses in exile with minimal interference by the authorities actually went out of their way to avoid being involved in any violent activity in Britain.

After all, they might need somewhere to escape to if the revolution didn’t play out the way they expected.

And the Okhrana, the Tsar’s secret police, were in England as well, sometimes co-operating with the British police, sometimes carrying out what the KGB later called мокрые делы – wet jobs – assassinations, and sometimes, especially after Sidney Street and the Houndsditch murders, with the connivance of the authorities.

There were of course other sorts of dissidents, ones like Sergei Stepniak, who was a gentleman, who spoke nicely about literature and art, quite unlike these strange slightly frightening men with strong accents and and their talk of violence and revolution, and who attracted groups of supporters such as the Friends of Russian Freedom. (While its helpful to think of the various factions within the dissident community as separate groupings there was a continuum – Fanny Stepniak, Sergei Stepniak’s widow helped organise Lenin’s 1907 RSDLP congress in London.)

And some of these supporters helped the dissidents by smuggling banned books and pamphlets into Russia.

Constance Garnett did so, and was so frightened by the experience she dumped all the material she was smuggling and escaped back to Britain as quickly as possible.

Russia was a frightening place where frightening, violent, things happened.

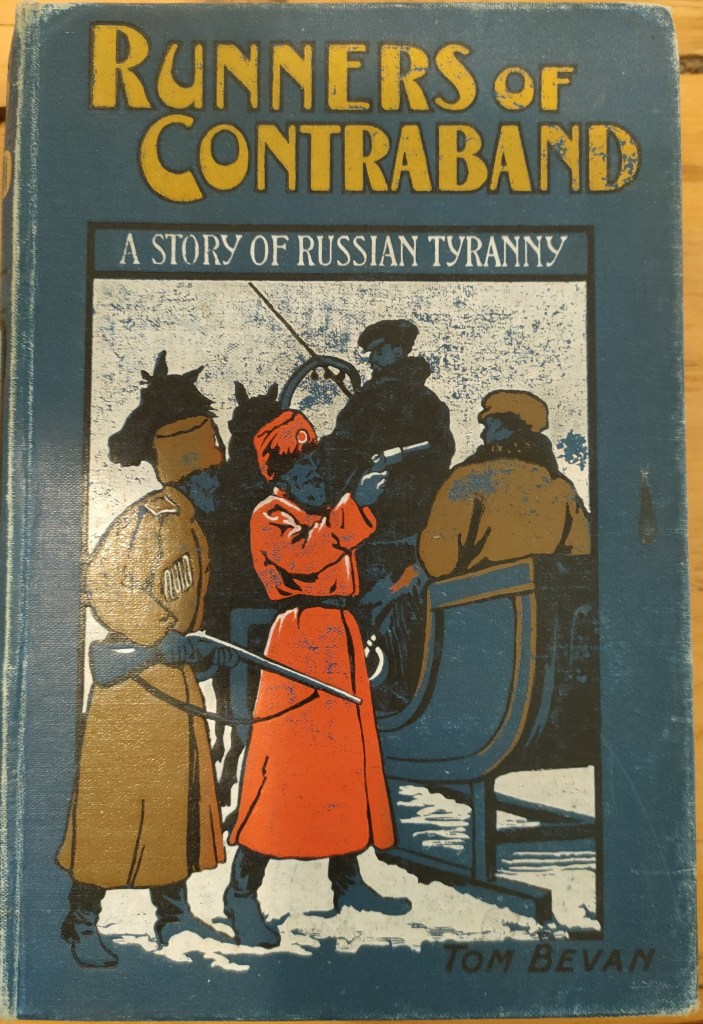

And this was reflected in the espionage fiction of the time. Hence novels like Tom Bevan’s Runners of Contraband, a tale of smuggling forbidden books and other material into Russia.

It’s probably not great fiction, but just as during the cold war bookshops always had a shelf or two of espionage fiction, it’s a symptom of how Russia was viewed by the Edwardians…