Over the last few days I’ve been reading Ursula Bloom’s memoir of her life as a young woman during the first world war.

It’s not history, it’s very much a personal memoir, but on another level it is an important resource describing how people in Britain on the Home Front felt about the war and a developing sense of cynicism about its progress.

Much of British World War One history focuses on generals, the hell of the Western Front, and very little on how people at home in Britain felt.

Bloom’s memoir helps correct that.

A clergyman’s daughter, living with her slowly dying mother, first in St Albans and then in Walton on the Naze in Essex, Bloom was a member of the genteel poor of the Edwardian era, living on a small fixed income which she supplemented by playing piano to accompany silent films in the cinema, she started the war full of the Edwardian certainties of Britain’s position in the world.

But when the army didn’t perform as well as expected, not to mention the navy, doubts began to creep in as to how well the war was actually going. Even the Daily Mail, Bloom’s newspaper of choice, couldn’t manage to maintain an upbeat tone, especially when Field Postcards ceased to be a novelty and often brought news of a loved one being wounded and in a field hospital.

Bloom habitually refers to the new post-1914 volunteer army as ‘Fred Karno’s Army’ that replaced the British Expeditionary Force due to its disorganisation and the way it consisted of half trained squaddies commanded by officers straight out of public school – Fred Karno was a well known slapstick comedian of the time who had a touring troupe.

Bloom also describes the impact of inflation on the genteel precariat on fixed incomes – things that were affordable became unaffordable, and, coupled with increases in income tax, began to hollow out the bottom end of Edwardian middle class.

Households could no longer afford maids and cooks, and the Aunt Mildreds, who had formerly managed quite well on small fixed incomes found it increasingly hard to manage.

Rationing in a sense was their salvation, as they had to live on a poorer meaner diet than before, and shortages of meat and potatoes, among other things, helped disguise that they simply couldn’t afford meat every day.

Other things stand out. Living on the Essex coast, Bloom would sit, in the blackout, watching the Zeppelin raids on the Thames estuary.

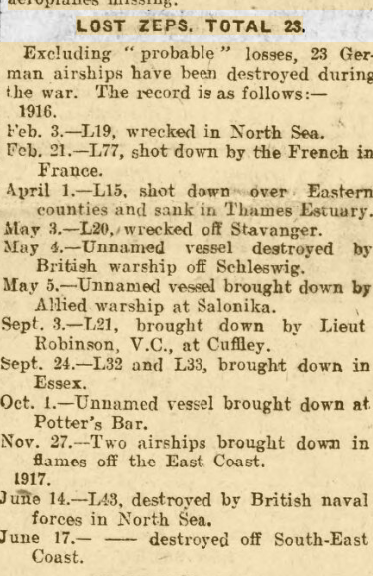

(As an aside I tried researching some of these raids using Welsh Newspapers Online. It’s quite clear from the reports that the British authorities heavily censored the reports of zeppelin raids, where they occurred and what damage there had been, perhaps for fear of spreading panic among the civilian population, or simply trying to curb war weariness.

On the other hand, perhaps because the Zeppelin raids worried the population so much, they were keen to publicise successes

As in the shooting down of L15, which Bloom witnessed. The Royal Flying Corps officer responsible for shooting down L15 was in fact from New Zealand, something the British papers seem not to mention, although it was headline news in New Zealand.)

As I say, an interesting resource, and a valuable counterweight to the ‘big men’ style of much of military history, especially where World One is concerned.

Pingback: Bicycle soldiers | stuff 'n other stuff