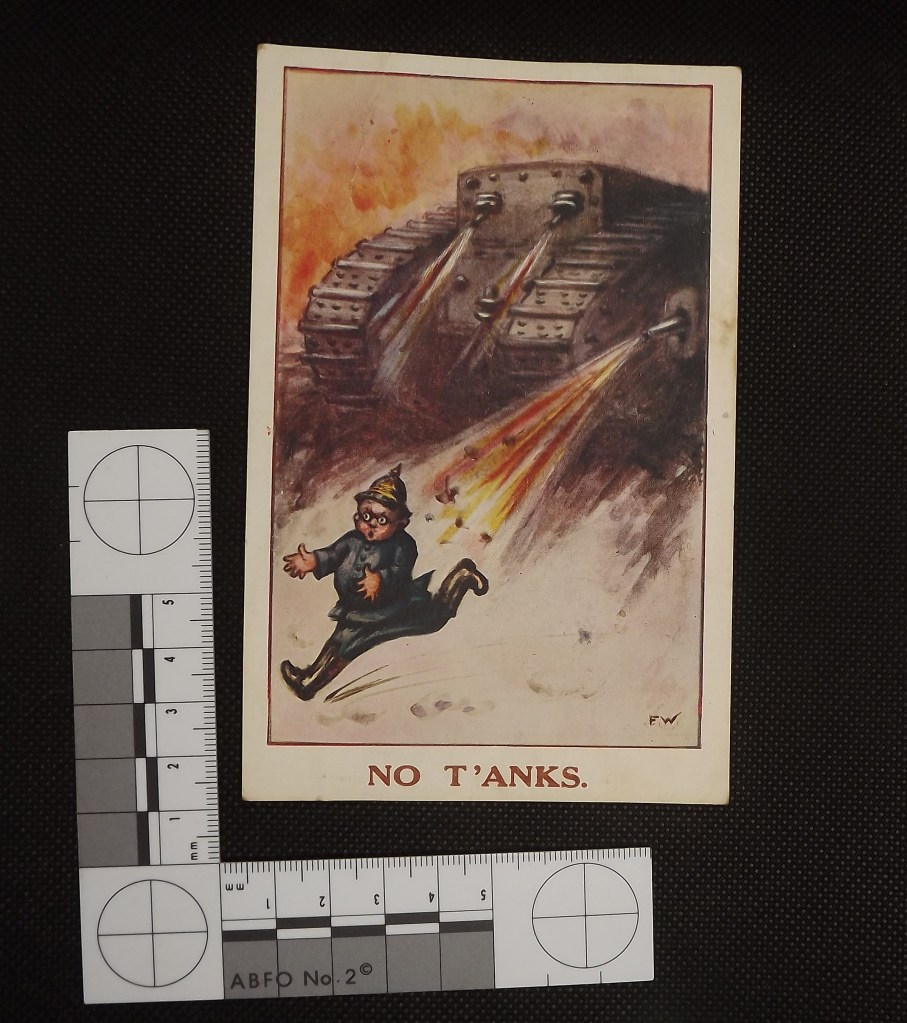

A nice example of a British propaganda card entitled ‘One of our tanks’ showing a British Mark IV tank

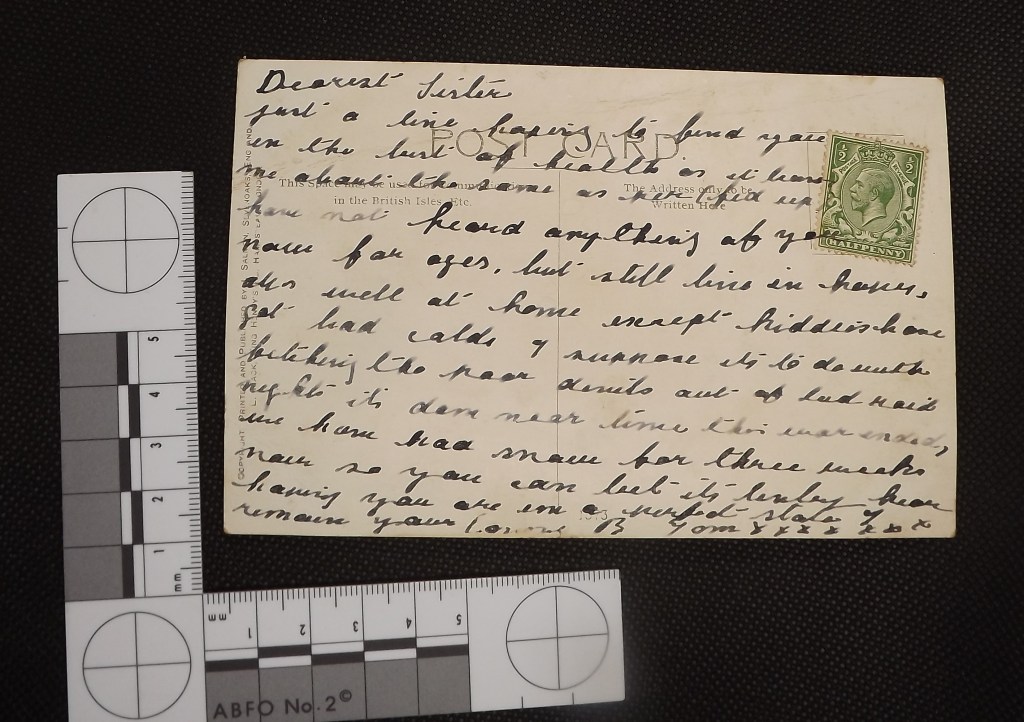

The text is quite legible and written in ink

My transcription of the text reads

Addressed to

Mrs Jas Souter

Tassetshill

Auchmacoy

Ellon

Posted

Aberdeen, 12.30PM Feb 5 1918 with standard George V 1/2d stamp

Message

This is the chap to swallow the notes! Hope you are all well, as we are here. How's Willie, he'll make a fine ploughman now. Tell him I was asking for him. From your loving nephew Mac.

Reverse illustration shows British Mark IV tank and caption

'copyright ELP Co - one of our tanks -passed by censor'

Auchmacoy still exists and is a farming estate outside of Ellon in Aberdeenshire. My first guess was that Tassetshill is a house or cottage name, or possibly a now disappeared fermtoun.

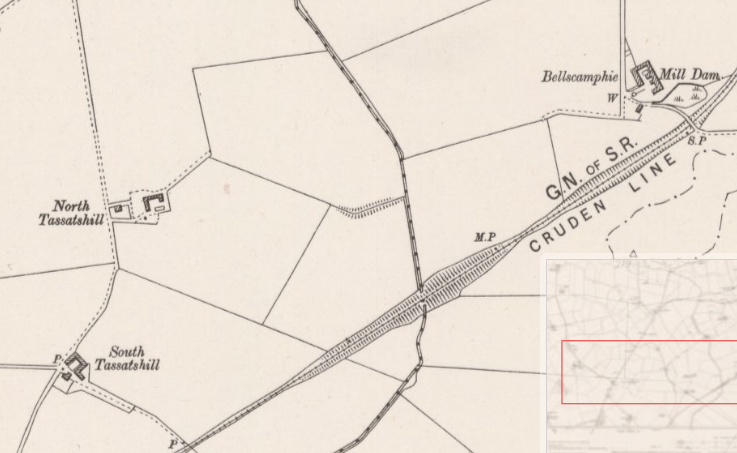

Google Maps only finds Auchmacoy, but the Royal Mail postcode finder admits to the existence of a South Tassetshill. The 1903 Ordnance Survey map shows Auchmacoy as a walled estate.

Tassethill lies a kilometre of two to the north east of Auchmacoy and, just to confuse things, is spelled Tassathill on the 1903 ordnance survey map and consists of a small settlement, probably a fermtoun (ie a group of farmworkers cottages clustered around a farmhouse and byres) to the north of Auchmacoy

Looking at a larger scale survey map from roughly the same period, this is confirmed with there being two fermtouns, north and south Tassatshill.

But the Royal Mail address finder only lists South Tassetshill. The 1965 Ordnance survey map still shows two groupings of buildings at Tassathill

My guess is that at some time in the last sixty or so years North Tassatshill was abandoned.

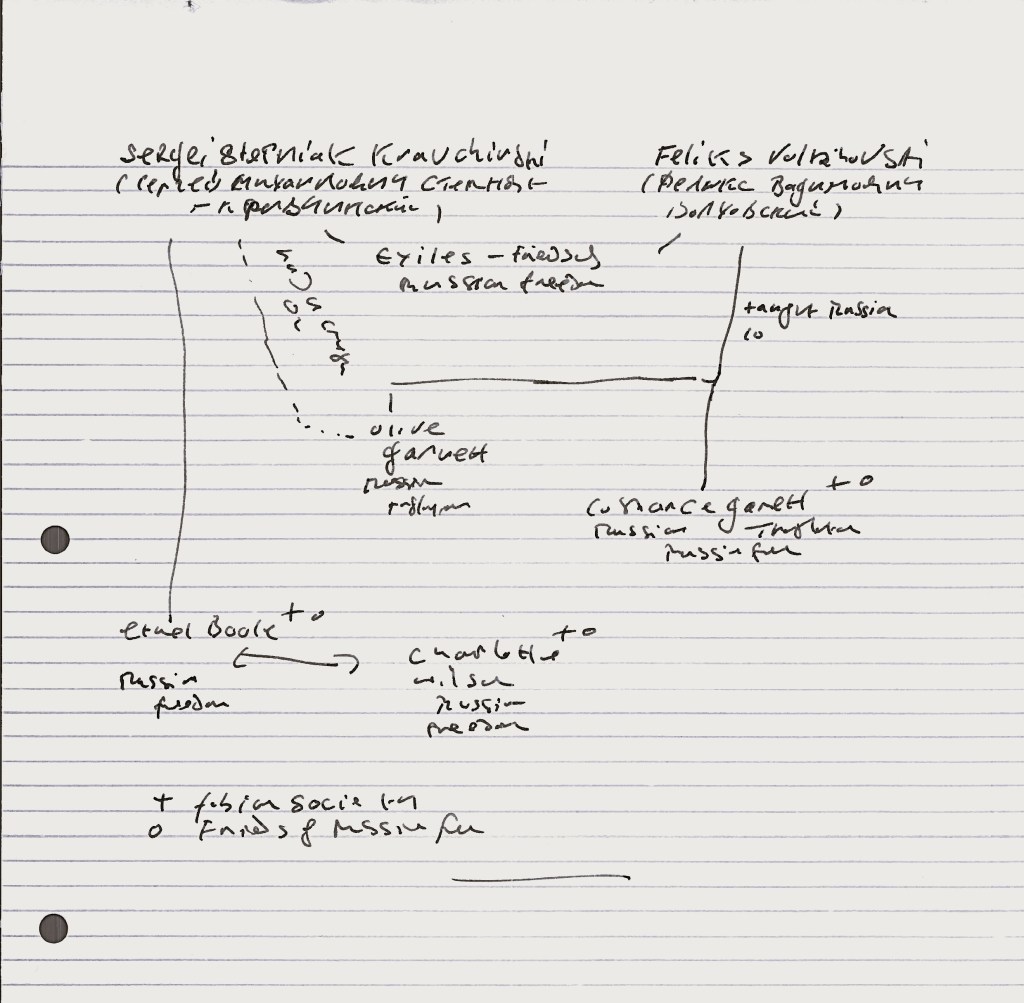

Scotlands people is not much help in identifying the addressee, there is no James Soutar (or his wife) listed in either the 1911 or 1921 census. This is not surprising as the land tenure system in the North East of Scotland meant that people would often move from job to job, rather than settling in one place.

The mention of Willie making a fine ploughman suggests that the Soutars were skilled agricultural workers, with a ploughman being a skilled occupation requiring the ploughman to be able to handle a team of heavy horses and plough a straight furrow – there even used to be annual ploughing championships where ploughmen competed for prize cups, and perhaps a small amount of cash.

As agricultural workers the Soutars would probably been exempt from conscription, as my grandfather, a tenant farmer further down the coast at St Cyrus was…